by Kenneth H Marks and Buddy Howard

One of the most often used metrics to value a private middle market business is EBITDA, which is earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. EBTIDA approximates cash flow (albeit on a pretax basis), which is the ultimate value driver for a business. One variation of EBITDA is adjusted EBITDA, which attempts to normalize “cash flow” by eliminating unusual, owner- related or nonrecurring items. Normalized EBITDA attempts to eliminate the financial noise and peculiarities of privately held companies in both the sell-side and buy-side transaction processes.

With the onset of COVID-19 and the associated economic shutdown, there has been a significant impact on most companies’ revenues, earnings, and EBITDA. While some businesses (such as the eat-at-home food industry, telehealth, communications, etc.), have “benefitted” from COVID-19, many companies have had severe negative effects from the pandemic. As a result, there has been an increasing trend to use a third, new metric: EBITDAC, for valuation purposes. EBITDAC is defined as the traditional normalized EBITDA measure except that it eliminates COVID effects, thus addition of the “C”.

What are those COVID-19 effects and how do you measure them? For many companies, the most immediate impact has been on revenues. Lost sales from closures, displaced key personnel, lower demand, as well as potential pricing concessions and order cancellations have all contributed to drops in companies’ revenues.

That loss of revenues often has a disproportionately negative affect on EBITDA since many expenses (rent, utilities, etc.) stay the same even on the lower revenues. Revenues may be off by 20%, while EBITDA may decline 50% to 60%, or even become negative.

There are a couple of ways to adjust EBITDA to derive a more “normalized” EBITDAC. One approach is to show the hypothetical (pro forma) revenues using the year-ago figures instead of the COVID-affected ones, possibly even adjusting for the pre-pandemic growth trends. For example, in arriving at normalized six-month revenues as of June 30, 2020, one could take the first two months of revenues from 2020, and add the revenues from March 1, 2019 through June 30, 2019, as adjusted for the growth that was evident from the first two months of 2020 relative to the year-ago numbers. In other words, if the revenues in the first two months were up 10%, one could increase the March 1, 2019 through June 30, 2019 revenues by the same amount and add this to actual revenues for the first two months of 2020. A more conservative approach would be to simply add the year-ago revenues without the growth. Also, try to identify/footnote your assumptions to ensure better transparency.

On the expense side, the best approach is often to multiply the pro forma level of revenues by the historical percentage of revenues that each expense represents. So, if general and administrative expense have historically been 20% of revenues, that is the percentage used on the pro forma revenues. Either way, the objective is to estimate what the financial results would have been had COVID-19 not existed.

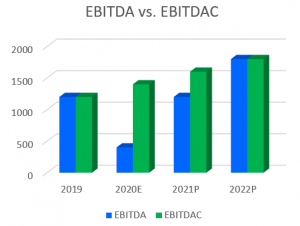

Assuming a vaccine is discovered and life returns to something resembling “normal” in the next year or two, the differences between EBITDA and EBITDAC will likely diminish in future periods, with 2020 (and possibly 2021) being the year(s) where there are the greatest differences. But the point is that during these interim years, using a measure that shows the normalized cash flow of the business can be critical from a seller’s standpoint.

Finally, it is often useful to show traditional measures such as EBITDA along with these new measures such as EBITDAC. In addition to quantifying COVID’s impact, tracking both will better measure the company’s progress as it returns to a normal performance.